S Constitution Art Iii Section I How It Works

Commodity 3 of the U.s.a. Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the federal authorities. Under Article Three, the judicial co-operative consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congress. Article Iii empowers the courts to handle cases or controversies arising nether federal law, likewise as other enumerated areas. Article Three also defines treason.

Department 1 of Article Three vests the judicial power of the United States in the Supreme Court, as well every bit junior courts established past Congress. Forth with the Vesting Clauses of Article One and Article Two, Article Three'south Vesting Clause establishes the separation of powers betwixt the three branches of government. Department 1 authorizes the creation of inferior courts, but does non crave it; the first junior federal courts were established shortly after the ratification of the Constitution with the Judiciary Deed of 1789. Section 1 likewise establishes that federal judges do not confront term limits, and that an individual judge's salary may non be decreased. Article Three does not set the size of the Supreme Court or establish specific positions on the courtroom, merely Article 1 establishes the position of chief justice.

Department 2 of Article 3 delineates federal judicial power. The Instance or Controversy Clause restricts the judiciary'south power to bodily cases and controversies, pregnant that federal judicial power does not extend to cases which are hypothetical, or which are proscribed due to standing, mootness, or ripeness issues. Section ii states that federal judiciary'south power extends to cases arising nether the Constitution, federal laws, federal treaties, controversies involving multiple states or foreign powers, and other enumerated areas. Section 2 gives the Supreme Courtroom original jurisdiction when ambassadors, public officials, or us are a political party in the instance, leaving the Supreme Courtroom with appellate jurisdiction in all other areas to which the federal judiciary's jurisdiction extends. Department 2 as well gives Congress the power to strip the Supreme Court of appellate jurisdiction, and establishes that all federal crimes must be tried earlier a jury. Department ii does not expressly grant the federal judiciary the ability of judicial review, only the courts accept exercised this power since the 1803 case of Marbury 5. Madison.

Department 3 of Article 3 defines treason and empowers Congress to punish treason. Section 3 requires that at least two witnesses testify to the treasonous deed, or that the individual defendant of treason confess in open up court. Information technology besides limits the ways in which Congress can punish those convicted of treason.

Section i: Federal courts [edit]

Section one is one of the three vesting clauses of the United States Constitution, which vests the judicial ability of the United States in federal courts, requires a supreme courtroom, allows junior courts, requires skillful behavior tenure for judges, and prohibits decreasing the salaries of judges.

The judicial Power of the U.s., shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such junior Courts as the Congress may from fourth dimension to time ordain and constitute. The Judges, both of the supreme and junior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services a Compensation which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

Clause ane: Vesting of judicial power and number of courts [edit]

Article III authorizes one Supreme Courtroom, but does not ready the number of justices that must be appointed to it. Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 refers to a Primary Justice (who shall preside over the impeachment trial of the President of the United states of america). Since 1869 the number of justices has been fixed at ix (by the Judiciary Act of 1869): one master justice, and eight associate justices.[1]

Proposals take been made at various times for organizing the Supreme Court into separate panels; none garnered broad support, thus the constitutionality of such a division is unknown. Even so, in a 1937 letter (to Senator Burton Wheeler during the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill debate), Master Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote, "the Constitution does non announced to authorize two or more Supreme Courts functioning in effect as separate courts."[2]

The Supreme Courtroom is the just federal courtroom that is explicitly established by the Constitution. During the Ramble Convention, a proposal was made for the Supreme Courtroom to be the only federal court, having both original jurisdiction and appellate jurisdiction. This proposal was rejected in favor of the provision that exists today. The Supreme Court has interpreted this provision as enabling Congress to create inferior (i.e., lower) courts under both Commodity 3, Section 1, and Article I, Department eight. The Article III courts, which are also known every bit "constitutional courts", were first created by the Judiciary Human action of 1789, and are the only courts with judicial ability. Article I courts, which are also known as "legislative courts", consist of regulatory agencies, such as the United States Tax Court.

In certain types of cases, Article 3 courts may practice appellate jurisdiction over Commodity I courts. In Murray's Lessee v. Hoboken Land & Improvement Co. (59 U.Due south. (xviii How.) 272 (1856)), the Court held that "at that place are legal matters, involving public rights, which may exist presented in such grade that the judicial power is capable of interim on them," and which are susceptible to review by an Commodity III court. After, in Ex parte Bakelite Corp. (279 U.S. 438 (1929)), the Courtroom declared that Article I courts "may be created every bit special tribunals to examine and decide various matters, arising between the regime and others, which from their nature do not crave judicial determination and yet are susceptible of information technology."[2] Other cases, such every bit bankruptcy cases, have been held not to involve judicial conclusion, and may therefore go before Article I courts. Similarly, several courts in the Commune of Columbia, which is under the sectional jurisdiction of the Congress, are Article I courts rather than Commodity III courts. This article was expressly extended to the U.s. District Courtroom for the District of Puerto Rico by the U.Southward. Congress through Federal Law 89-571, 80 Stat. 764, signed past President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966. This transformed the article Four United States territorial court in Puerto Rico, created in 1900, to an Article Three federal judicial commune court.

The Judicial Procedures Reform Pecker of 1937, frequently called the court-packing programme,[3] was a legislative initiative to add together more justices to the Supreme Court proposed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt shortly after his victory in the 1936 presidential election. Although the nib aimed generally to overhaul and modernize the entire federal courtroom system, its central and almost controversial provision would take granted the President ability to appoint an additional justice to the Supreme Court for every incumbent justice over the age of seventy, upwardly to a maximum of 6.[4]

The Constitution is silent when information technology comes to judges of courts which take been abolished. The Judiciary Act of 1801 increased the number of courts to permit the Federalist President John Adams to appoint a number of Federalist judges earlier Thomas Jefferson took office. When Jefferson became President, the Congress abolished several of these courts and fabricated no provision for the judges of those courts. The Judicial Code of 1911 abolished circuit riding and transferred the circuit courts authority and jurisdiction to the district courts.

Clause 2: Tenure [edit]

The Constitution provides that judges "shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour." The term "expert behaviour" is interpreted to hateful that judges may serve for the remainder of their lives, although they may resign or retire voluntarily. A judge may also be removed by impeachment and conviction past congressional vote (hence the term proficient behaviour); this has occurred fourteen times. Three other judges, Mark W. Delahay,[v] George W. English language,[6] and Samuel B. Kent,[seven] chose to resign rather than go through the impeachment process.

Clause three: Salaries [edit]

The bounty of judges may not be decreased, but may be increased, during their constancy in role.

Department ii: Judicial power, jurisdiction, and trial past jury [edit]

Section 2 delineates federal judicial ability, and brings that power into execution by conferring original jurisdiction and also appellate jurisdiction upon the Supreme Courtroom. Additionally, this department requires trial past jury in all criminal cases, except impeachment cases.

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Police and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, nether their Authority;—to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls;—to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction;—to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party;—to Controversies between ii or more States;—between a Land and Citizens of another State;—between Citizens of different States;—betwixt Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and betwixt a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall exist Party, the supreme Courtroom shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall accept appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall accept been committed; only when not committed inside any Land, the Trial shall exist at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Police have directed.

Clause 1: Cases and controversies [edit]

Clause 1 of Section ii authorizes the federal courts to hear actual cases and controversies only. Their judicial power does not extend to cases which are hypothetical, or which are proscribed due to standing, mootness, or ripeness issues. Generally, a case or controversy requires the presence of adverse parties who have a 18-carat interest at stake in the case. In Muskrat five. U.s., 219 U.S. 346 (1911), the Supreme Court denied jurisdiction to cases brought nether a statute permitting certain Native Americans to bring suit against the United States to determine the constitutionality of a law allocating tribal lands. Counsel for both sides were to be paid from the federal Treasury. The Supreme Court held that, though the United States was a defendant, the case in question was not an actual controversy; rather, the statute was merely devised to test the constitutionality of a certain type of legislation. Thus the Court's ruling would be zip more than an advisory opinion; therefore, the court dismissed the adjust for failing to present a "instance or controversy."

A significant omission is that although Clause 1 provides that federal judicial ability shall extend to "the laws of the United States," it does not besides provide that it shall extend to the laws of the several or individual states. In plough, the Judiciary Act of 1789 and subsequent acts never granted the U.S. Supreme Court the power to review decisions of state supreme courts on pure problems of state law. It is this silence which tacitly fabricated state supreme courts the concluding expositors of the common police in their respective states. They were free to diverge from English precedents and from each other on the vast majority of legal problems which had never been made part of federal law past the Constitution, and the U.Due south. Supreme Courtroom could do nothing, as it would ultimately concede in Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins (1938). Past mode of dissimilarity, other English-speaking federations like Commonwealth of australia and Canada never adopted the Erie doctrine. That is, their highest courts have e'er possessed plenary power to impose a uniform nationwide common law upon all lower courts and never adopted the strong American distinction between federal and state common police.

Eleventh Amendment and land sovereign immunity [edit]

In Chisholm five. Georgia, ii U.Due south. 419 (1793), the Supreme Court ruled that Article 3, Section 2 abrogated the States' sovereign immunity and authorized federal courts to hear disputes between private citizens and States. This decision was overturned by the Eleventh Subpoena, which was passed past the Congress on March 4, 1794 1 Stat. 402 and ratified past usa on February 7, 1795. It prohibits the federal courts from hearing "any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted confronting ane of the United States by Citizens of another Land, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Strange Land".[eight]

Clause two: Original and appellate jurisdiction [edit]

Clause ii of Department 2 provides that the Supreme Courtroom has original jurisdiction in cases affecting ambassadors, ministers and consuls, and too in those controversies which are discipline to federal judicial ability considering at least one country is a party; the Court has held that the latter requirement is met if the U.s.a. has a controversy with a state.[9] [10] In other cases, the Supreme Court has only appellate jurisdiction, which may exist regulated by the Congress. The Congress may not, notwithstanding, amend the Court's original jurisdiction, as was found in Marbury 5. Madison, v U.S. (Cranch 1) 137 (1803) (the same determination which established the principle of judicial review). Marbury held that Congress tin can neither expand nor restrict the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. However, the appellate jurisdiction of the Court is unlike. The Court'southward appellate jurisdiction is given "with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Congress shall brand."

Often a courtroom volition assert a modest degree of ability over a case for the threshold purpose of determining whether it has jurisdiction, and so the word "ability" is non necessarily synonymous with the give-and-take "jurisdiction".[11] [12]

Judicial review [edit]

The power of the federal judiciary to review the constitutionality of a statute or treaty, or to review an administrative regulation for consistency with either a statute, a treaty, or the Constitution itself, is an implied power derived in part from Clause 2 of Section two.[thirteen]

Though the Constitution does non expressly provide that the federal judiciary has the ability of judicial review, many of the Constitution'southward Framers viewed such a power as an advisable ability for the federal judiciary to possess. In Federalist No. 78, Alexander Hamilton wrote,

The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution, is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, every bit a primal law. Information technology therefore belongs to them to define its significant, besides equally the significant of any detail act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to exist an irreconcilable variance between two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.[14]

Hamilton goes on to weigh the tone of "judicial supremacists," those enervating that both Congress and the Executive are compelled by the Constitution to enforce all court decisions, including those that, in their eyes, or those of the People, violate central American principles:

Nor does this conclusion by whatever means suppose a superiority of the judicial to the legislative power. It only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both; and that where the will of the legislature, declared in its statutes, stands in opposition to that of the people, declared in the Constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter rather than the quondam. They ought to regulate their decisions by the fundamental laws, rather than by those which are not fundamental.[14] It can exist of no weight to say that the courts, on the pretense of a repugnancy, may substitute their own pleasure to the constitutional intentions of the legislature. This might as well happen in the case of 2 contradictory statutes; or it might as well happen in every adjudication upon any single statute. The courts must declare the sense of the constabulary; and if they should be tending to exercise will instead of judgement, the consequence would equally be the substitution of their pleasure to that of the legislative body. The observation, if information technology testify any matter, would prove that there ought to be no judges distinct from that torso.[xiv]

Marbury v. Madison involved a highly partisan set of circumstances. Though Congressional elections were held in November 1800, the newly elected officers did not take power until March. The Federalist Party had lost the elections. In the words of President Thomas Jefferson, the Federalists "retired into the judiciary as a stronghold". In the four months post-obit the elections, the outgoing Congress created several new judgeships, which were filled past President John Adams. In the last-infinitesimal rush, however, Federalist Secretary of State John Marshall had neglected to deliver 17 of the commissions to their respective appointees. When James Madison took office every bit Secretarial assistant of State, several commissions remained undelivered. Bringing their claims under the Judiciary Act of 1789, the appointees, including William Marbury, petitioned the Supreme Court for the event of a writ of mandamus, which in English language law had been used to force public officials to fulfill their ministerial duties. Here, Madison would exist required to evangelize the commissions.

Marbury posed a difficult trouble for the court, which was and then led by Chief Justice John Marshall, the same person who had neglected to evangelize the commissions when he was the Secretarial assistant of Country. If Marshall's court commanded James Madison to deliver the commissions, Madison might ignore the order, thereby indicating the weakness of the court. Similarly, if the court denied William Marbury's request, the court would be seen as weak. Marshall held that appointee Marbury was indeed entitled to his commission. However, Justice Marshall contended that the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional, since it purported to grant original jurisdiction to the Supreme Court in cases not involving u.s. or ambassadors[ citation needed ]. The ruling thereby established that the federal courts could exercise judicial review over the deportment of Congress or the executive co-operative.

However, Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist No. 78, expressed the view that the Courts hold only the ability of words, and not the power of compulsion upon those other two branches of government, upon which the Supreme Court is itself dependent. Then in 1820, Thomas Jefferson expressed his deep reservations about the doctrine of judicial review:

Y'all seem ... to consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions; a very unsafe doctrine indeed, and ane which would place usa under the despotism of an oligarchy. Our judges are every bit honest as other men, and not more than and then. They have, with others, the aforementioned passions for party, for power, and the privilege of their corps ... Their ability [is] the more dangerous as they are in office for life, and not responsible, equally the other functionaries are, to the elective command. The Constitution has erected no such single tribunal, knowing that to whatsoever hands confided, with the corruptions of time and party, its members would get despots. It has more wisely made all the departments co-equal and co-sovereign within themselves.[15]

Clause 3: Federal trials [edit]

A nineteenth-century painting of a jury

Clause 3 of Section 2 provides that Federal crimes, except impeachment cases, must exist tried before a jury, unless the defendant waives their correct. Also, the trial must be held in the country where the criminal offense was committed. If the crime was not committed in any particular land, then the trial is held in such a identify every bit prepare along past the Congress. The United States Senate has the sole power to endeavour impeachment cases.[16]

Two of the Ramble Amendments that incorporate the Pecker of Rights contain related provisions. The 6th Amendment enumerates the rights of individuals when facing criminal prosecution and the Seventh Subpoena establishes an individual'due south right to a jury trial in certain civil cases. It too inhibits courts from overturning a jury's findings of fact. The Supreme Courtroom has extended the right to a jury in the 6th Amendment to individuals facing trial in state courts through the Due Procedure Clause of the Fourteenth Subpoena, but has refused to practise and then with the Seventh.

Section three: Treason [edit]

Section 3 defines treason and limits its penalisation.

Treason against the U.s.a., shall consist only in levying State of war against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Condolement. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court. The Congress shall take Power to declare the Punishment of Treason, merely no Attainder of Treason shall piece of work Corruption of Blood, or Forfeiture except during the Life of the Person attainted.

The Constitution defines treason as specific acts, namely "levying State of war confronting [the United states], or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort." A contrast is therefore maintained with the English law, whereby crimes including conspiring to kill the King or "violating" the Queen, were punishable as treason. In Ex Parte Bollman, viii U.S. 75 (1807), the Supreme Courtroom ruled that "there must be an actual assembling of men, for the treasonable purpose, to establish a levying of war."[17]

Nether English law effective during the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, at that place were several species of treason. Of these, the Constitution adopted only ii: levying war and adhering to enemies. Omitted were species of treason involving encompassing (or imagining) the expiry of the king, sure types of counterfeiting, and finally fornication with women in the royal family unit of the sort which could call into question the parentage of royal successors. James Wilson wrote the original draft of this section, and he was involved every bit a defence force attorney for some accused of treason against the Patriot cause. The 2 forms of treason adopted were both derived from the English language Treason Act 1351. Joseph Story wrote in his Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States of the authors of the Constitution that:

they have adopted the very words of the Statute of Treason of Edward the Third; and thus by implication, in social club to cut off at once all chances of arbitrary constructions, they accept recognized the well-settled interpretation of these phrases in the administration of criminal constabulary, which has prevailed for ages.[eighteen]

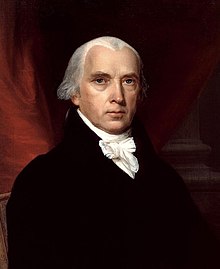

In Federalist No. 43 James Madison wrote regarding the Treason Clause:

As treason may be committed against the United States, the authorization of the United States ought to be enabled to punish it. Only equally new-fangled and artificial treasons have been the peachy engines by which tearing factions, the natural offspring of free government, accept usually wreaked their alternating malignity on each other, the convention have, with great judgment, opposed a barrier to this peculiar danger, by inserting a constitutional definition of the crime, fixing the proof necessary for conviction of it, and restraining the Congress, fifty-fifty in punishing it, from extending the consequences of guilt across the person of its writer.

Based on the above quotation, information technology was noted by the lawyer William J. Olson in an amicus curiae in the case Hedges v. Obama that the Treason Clause was ane of the enumerated powers of the federal authorities.[nineteen] He also stated that by defining treason in the U.S. Constitution and placing it in Article Three "the founders intended the power to be checked past the judiciary, ruling out trials by armed services commissions. As James Madison noted, the Treason Clause also was designed to limit the power of the federal government to punish its citizens for 'adhering to [the] enemies [of the United States past], giving them assistance and comfort.'"[19]

Section three also requires the testimony of two different witnesses on the same overt act, or a confession by the defendant in open court, to convict for treason. This dominion was derived from another English statute, the Treason Act 1695.[20] The English law did not require both witnesses to have witnessed the aforementioned overt act; this requirement, supported by Benjamin Franklin, was added to the typhoon Constitution by a vote of 8 states to three.[21]

In Cramer v. United States, 325 U.South. i (1945), the Supreme Court ruled that "[eastward]very human activity, movement, deed, and word of the defendant charged to institute treason must exist supported by the testimony of ii witnesses."[22] In Haupt five. United States, 330 U.S. 631 (1947), even so, the Supreme Court found that two witnesses are not required to bear witness intent, nor are two witnesses required to prove that an overt deed is treasonable. The two witnesses, according to the decision, are required to prove only that the overt act occurred (eyewitnesses and federal agents investigating the crime, for example).

Penalty for treason may non "piece of work Corruption of Blood, or Forfeiture except during the Life of the Person" so convicted. The descendants of someone convicted for treason could not, as they were under English language law, be considered "tainted" by the treason of their ancestor. Furthermore, Congress may confiscate the holding of traitors, but that property must exist inheritable at the death of the person convicted. [ commendation needed ]

See also [edit]

- U.s. constitutional criminal procedure

- List of current Us Circuit Judges

References [edit]

- ^ "Landmark Legislation: Excursion Judgeships". Washington, D.C.: Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Constitution of the U.s.: Analysis, and Interpretation – Centennial Edition – Interim" (PDF). S. Doc. 112-9. Washington, D.C.: U.South. Regime Printing Part. p. 639. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ Epstein, Lee; Walker, Thomas G. (2007). Constitutional Police force for a Changing America: Institutional Powers and Constraints (sixth ed.). Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-933116-81-5., at 451.

- ^ "Feb 05, 1937: Roosevelt announces "court-packing" plan". This Day in History. A&E Networks. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ "Judges of the United states of america Courts – Delahay, Marker W." Federal Judicial Center. northward.d. Retrieved 2009-07-02 .

- ^ staff (n.d.). "Judges of the United states Courts – English language, George Washington". Federal Judicial Eye. Retrieved 2009-07-02 .

- ^ "Judges of the United States Courts – Kent, Samuel B." Federal Judicial Heart. n.d. Retrieved 2009-07-02 .

- ^ "Notation i – Eleventh Subpoena – Land Immunity". FindLaw . Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Usa v. Texas, 143 U.S. 621 (1892). A factor in United States v. Texas was that in that location had been an "human action of congress requiring the institution of this accommodate". With a few narrow exceptions, courts have held that Congress controls admission to the courts by the United States and its agencies and officials. See, e.g., Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co., 514 U.S. 122 ("Agencies practise non automatically have continuing to sue for actions that frustrate the purposes of their statutes"). Also see U.s. v. Mattson, 600 F. 2d 1295 (9th Cir. 1979).

- ^ Cohens v. Virginia, nineteen U.S. 264 (1821): "[T]he original jurisdiction of the Supreme court, in cases where a state is a party, refers to those cases in which, co-ordinate to the grant of power fabricated in the preceding clause, jurisdiction might be exercised, in consequence of the graphic symbol of the party."

- ^ Comprehend, Robert. Narrative, Violence and the Law (U. Mich. 1995): "Every denial of jurisdiction on the part of a court is an assertion of the power to determine jurisdiction..."

- ^ Di Trolio, Stefania. "Undermining and Unintwining: The Right to a Jury Trial and Rule 12(b)(1) Archived July v, 2011, at the Wayback Motorcar", Seton Hall Law Review, Volume 33, folio 1247, text accompanying notation 82 (2003).

- ^ "The Establishment of Judicial Review" Archived 2013-01-xv at the Wayback Machine. Findlaw.

- ^ a b c "The Federalist Papers : No. 78". Archived from the original on 29 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-ten-28 .

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Alphabetic character to William Jarvis (September 28, 1820).

- ^ U.S. Constitution, Art. I, sec. three

- ^ Bollman, at 126

- ^ Story, J. (1833) Commentaries sec. 1793

- ^ a b Olson, William J. (16 April 2012). "Case one:12-cv-00331-KBF Document 29-2 Filed 04/16/12 AMICUS CURIAE Cursory" (PDF). Friedman, Harfenist, Kraut & Perlstein, PPC. lawandfreedom.com. pp. 15–16.

- ^ This rule was abolished in the Great britain in 1945.

- ^ Madison, James (1902) The Writings of James Madison, vol. iv, 1787: The Journal of the Ramble Convention, Office II (edited by G. Chase), pp. 249–250

- ^ Cramer, at 34

Bibliography [edit]

- Irons, Peter (1999). A People'south History of the Supreme Court. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN978-0-14-303738-5.

External links [edit]

- CRS Annotated Constitution: Article 3, police.cornell.edu

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Article_Three_of_the_United_States_Constitution

0 Response to "S Constitution Art Iii Section I How It Works"

Post a Comment